Top: Cerastes vipera (a live-bearing viperid snake); bottom: Cerastes cerastes (an egg-laying congener). (Photo: Anna Zimin)

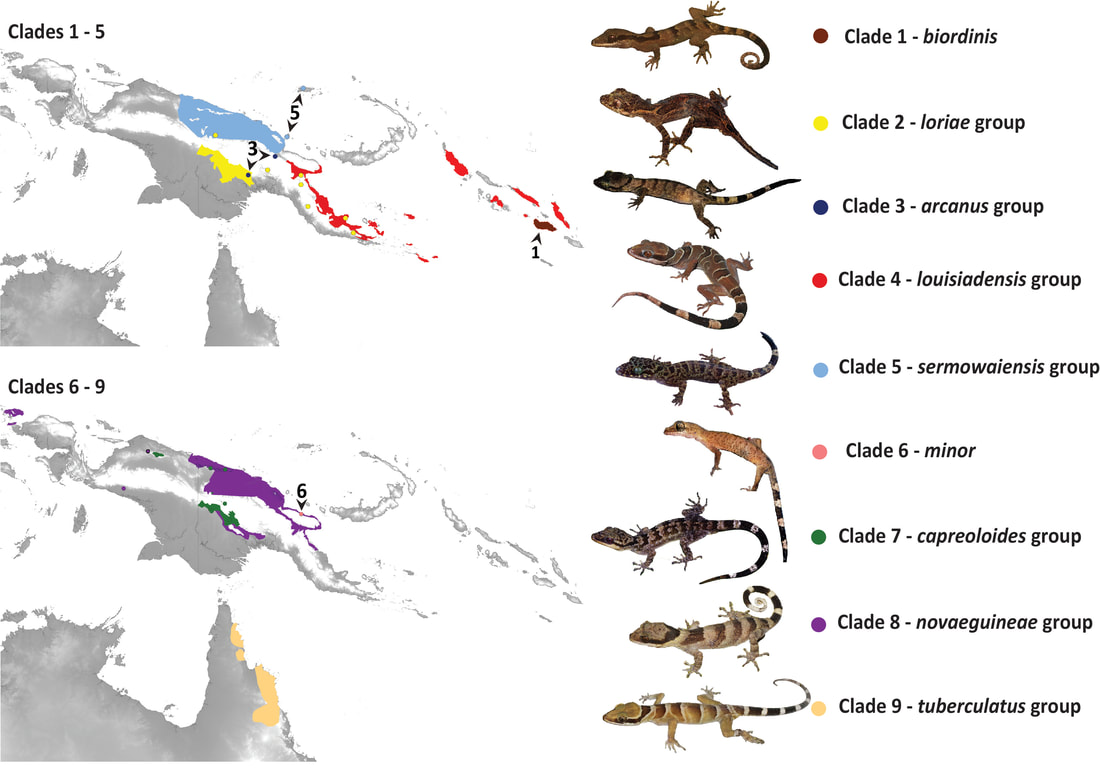

Top: Cerastes vipera (a live-bearing viperid snake); bottom: Cerastes cerastes (an egg-laying congener). (Photo: Anna Zimin) Vertebrates are known for their versatility in reproductive strategies and features. Those, in turn, facilitated their successful expansion across various types of environments worldwide. For instance, the evolution of shelled eggs promoted the expansion of tetrapods into terrestrial habitats, and the retention of eggs inside the parent’s body significantly improved embryo survivability in harsh environmental conditions. Live-bearing (henceforth ‘viviparity’) evolved across all major vertebrate groups, except birds, crocodilians and turtles. Whereas it evolved only once in the mammal history, it is thought to evolve over 100 times independently in squamates (lizards and snakes), with about 20% of their species being viviparous. The prevalence of both egg-laying (oviparity) and viviparity in many squamate clades, and the multiple origins of viviparity, make squamates an excellent model to study the selective forces behind the evolution and biogeography of reproductive modes.

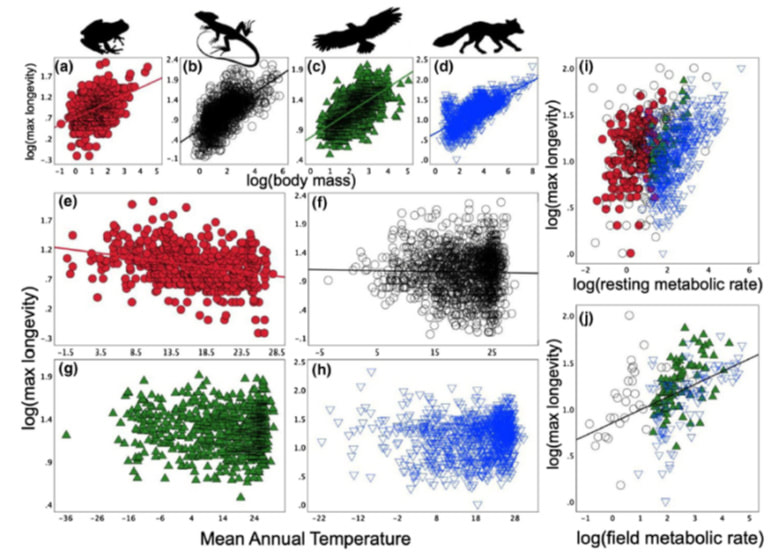

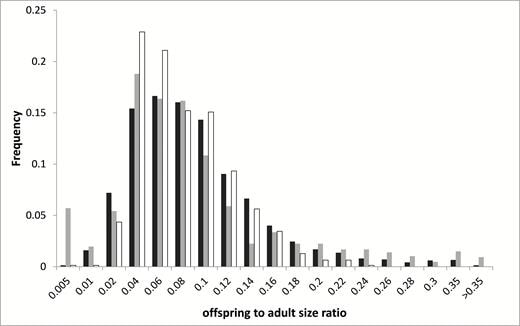

In this study, we aimed to examine most of the common selective forces hypothesized to drive the evolution of viviparity, and the relationship of reproductive mode with body size. Specifically, we tested the predictions that viviparity will be associated with (1) cold climates, (2) unpredictable climates, (3) high elevations (a proxy for hypoxic conditions), and (4) large adult body sizes. In order to do that, we collated a dataset for over 9,000 squamate species (about 80% of non-marine living species), making it the largest-scale study on the subject. Furthermore, because the factors mentioned above may be associated both directly and indirectly (i.e., through another factor) with reproductive mode, we used methods, such as path analysis, that enable to detect and account for such complex relationships.

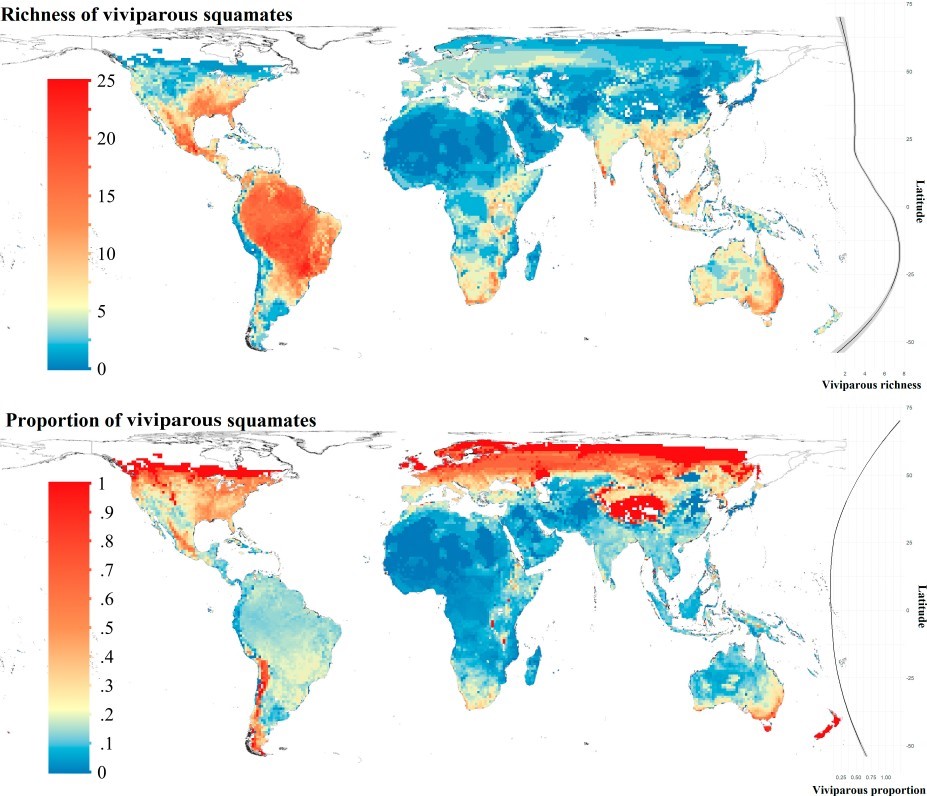

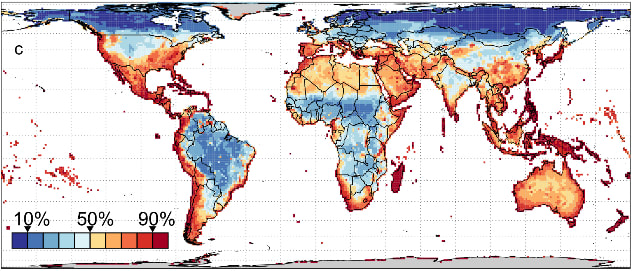

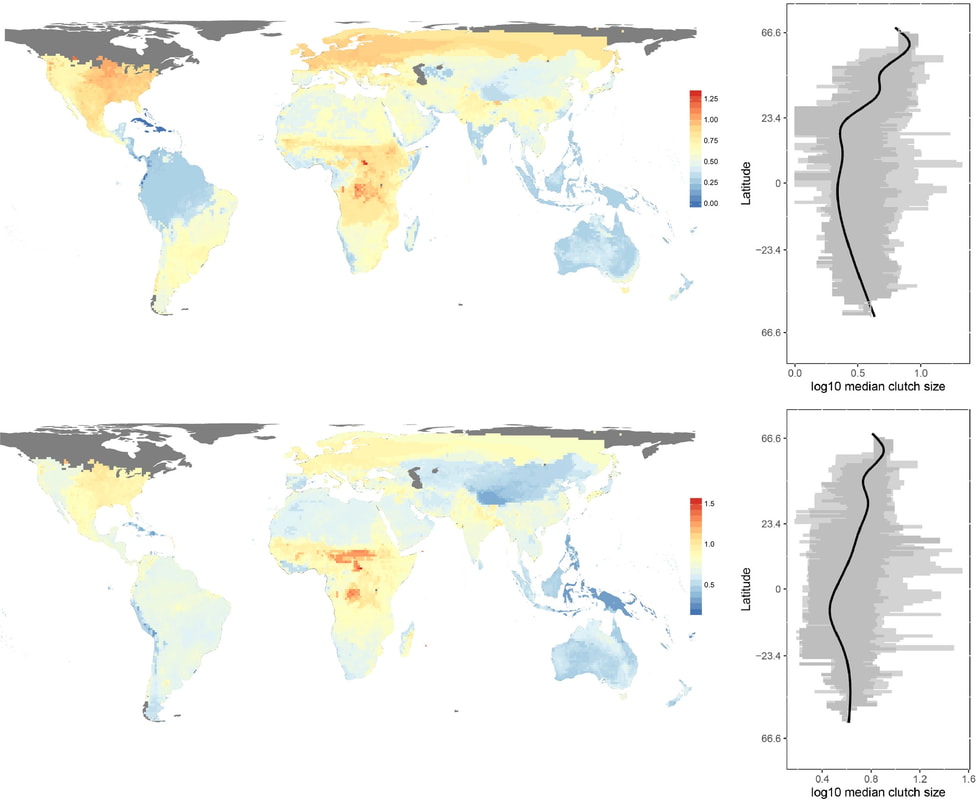

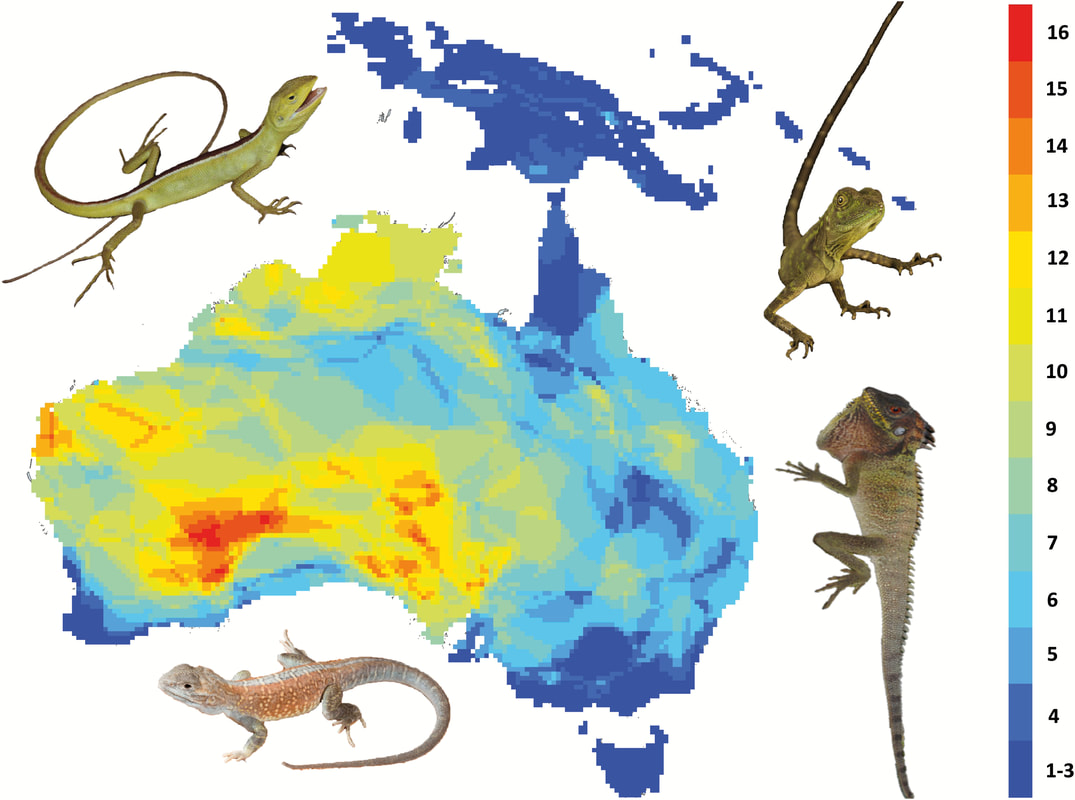

Our main finding was that viviparity was strongly associated with cold climates, in line with earlier studies. In fact, there are relatively more viviparous than oviparous species in colder climates, and some of the coldest regions occupied by squamates do not include oviparous species at all. Notably, although some warm regions harbor many viviparous species (much more than the coldest climates), such regions usually include even more egg-laying species. The roles of climatic variation and of elevation were found to be less important and not straightforward. Even though the proportions of viviparity at high elevations are higher, elevation probably exerts various selective pressures and influences the prevalence of viviparity primarily through its effect on temperature. Our findings highlight the complexity of processes potentially underlying the evolution of viviparity, but they also provide clear support for low temperatures as selecting for viviparity in squamates.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed