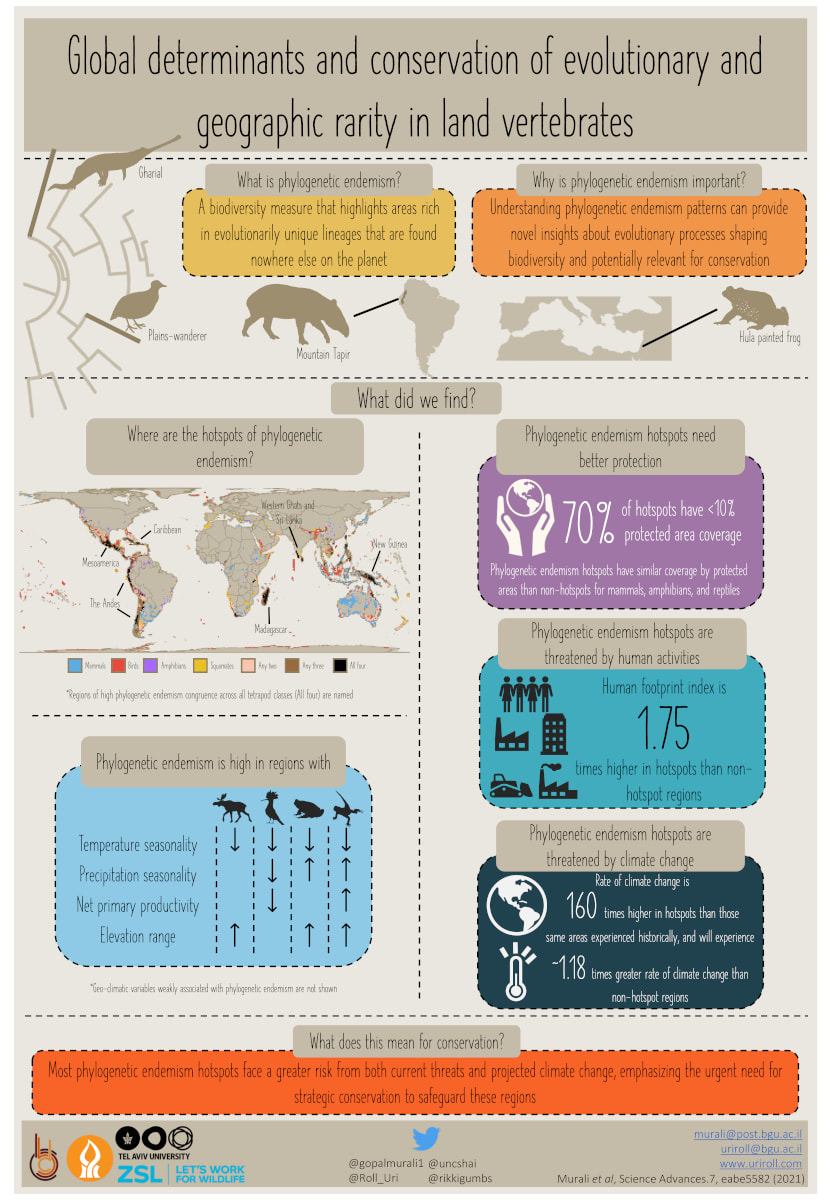

We live in the age of the ‘sixth mass extinction’. Our daily activities are causing hundreds and thousands of species to be lost forever. To turn the tide on the biodiversity crisis we have to identify those regions and species that are most in need of our conservation efforts. However, the characteristics of regions or species most in need of protection are not always clear. In this work we focus on those species that have two distinct features that make especially good candidates for conservation efforts. First – they are confined to only small and distinct location on the globe – what are known as endemic species and face greater risk of extinction. Second – they are evolutionary unique - they do not have close relatives on the ‘tree of life’ and their loss will represent a loss of millions of years of evolution. Species that poses both of these attributes (phylogenetic endemics) are therefore of great conservation importance as they represent unique and threatened components of biodiversity. To explore these species, we collected data regarding the evolutionary relationships and geographic distribution of almost all land vertebrate species (~30,000 species of amphibians, birds, mammals, and reptiles). We set out to map global ‘hotpots’ of such species, understand what are the unique conditions that support them, and evaluate their current protection and threats.

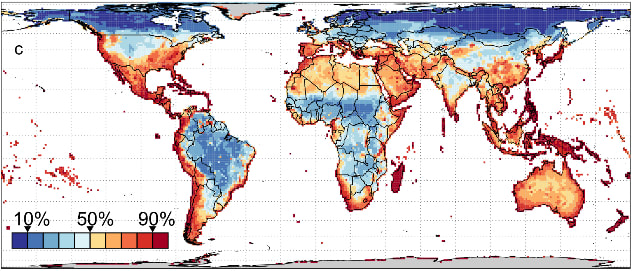

We found that hotspots of phylogenetically endemic species mostly occur in the tropics and in the southern hemisphere along mountain ranges and in islands. Altogether, these hotspots, when combining the hotspots for all of the four above-mentioned groups, they occupy 22% of the total landmass. Hotspots that were important for all of the four groups are located in the Caribbean islands, Central America, along the Andes, eastern Madagascar, Sri Lanka, southern Western Ghats in India, and New Guinea. Although some of these regions have been previously prioritized for conservation actions, our study also found hotspots outside well-known biodiversity centres. For instance, we found the Asir mountains in Saudi Arabia to be important for such unique birds and Morocco to harbour phylogenetically endemic reptiles. Globally, these regions are mostly defined as mountainous tropical regions. This finding supports the notion that tropical mountains have an important role in the generation and maintenance of biodiversity.

We next quantified how human activities and climate change are threatening these hotspots. Alarmingly, we found human activities such as buildings, roads, land-use, population density, and rate of climate change to be disproportionately higher in these hotspots (when compared to regions outside them). Consequently, our study highlights that many uniquely rare species, which probably perform important roles in the ecosystem, will be the first to be lost due to global change. Furthermore, we found most of the hotspots are not adequately protected. About 70% of the hotspots regions have less than 10% overlap with protected areas. Some of these regions which require urgent conservation action are the southern Andes, Horn of Africa, Southern Africa, and the Solomon Islands.

To-date most conservation strategies still focus on species-rich regions or flagship species, which may miss out on regions with uniquely rare species we identified. Overall, our study emphasizes on the need for strategic conservation policy and management to safeguard the persistence of thousands of small-ranged species that represent millions of years of unique evolutionary history.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed