The beginnings of GARD

Planning for reptile conservation globally we first needed to map the distribution of all known species. About 8500 of them when we started in 2006, about 10,500 now recognized. This was a time when such global databases were being published for amphibians, birds, and mammals – some of us have been instrumental in assembling those databases, so we felt fairly confident we knew how it should be done.

| What we were wondering, however, was whether the fact that reptile distributions were not collated at the time was not because it couldn’t be. A quick survey of available field guides and herpetology books revealed that maps of the sort used to assemble distribution data for birds and mammals were simply unavailable for huge parts of the world, including most of the crucial regions in tropical South America, Africa and Southern Asia. |

| Thus the Global Assessment of Reptile Distribution working group (GARD) was formed. In the meantime we started recruiting the people who did much of the actual legwork – graduate students who digitized maps from existing sources, as well as the maps that started pouring in from the reptile experts among the GARD members. We had to keep track with constant taxonomic changes, species splits and new reptile species discoveries (many of them by GARD members themselves) – resulting in additional 200 species or reptiles nowadays being added annually. |

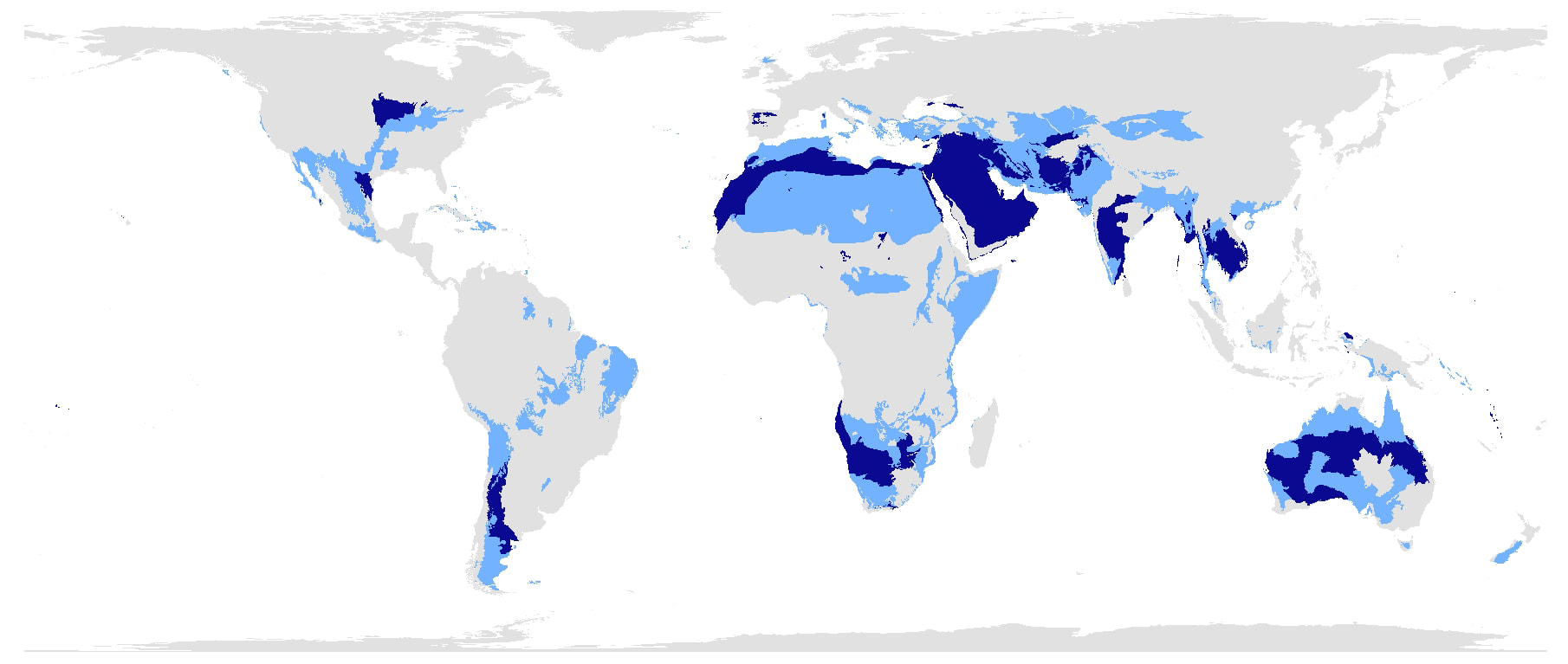

| Early on in compiling the data we got the feeling that lizard ‘hotspots’ were not in the tropics, where virtually all other groups studied so far have the most species. Once the maps were fully compiled this was very evident. The unique thermal requirements of reptiles enable them to thrive in drier habitats, allowing them to evolve and prosper in deserts. |

Or in other words do the major global conservation priorities designations adequately represent reptiles or do their unique distributions make them less protected. It turns out that many reptiles – predominantly lizards and turtles are left out of global priority regions and protected areas.

| We therefore wanted to explore how the focus of future conservation efforts need to change to properly represent reptiles. To do this we run prioritization optimization procedures which enabled us to highlight various regions of the world predominantly in drylands, savannah, steppe, and also islands that increase in importance when reptile distribution data are added. More broadly this work highlights the need of getting better data for lesser known groups in order to compile truly inclusive conservation planning that encapsulates all of biodiversity. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed