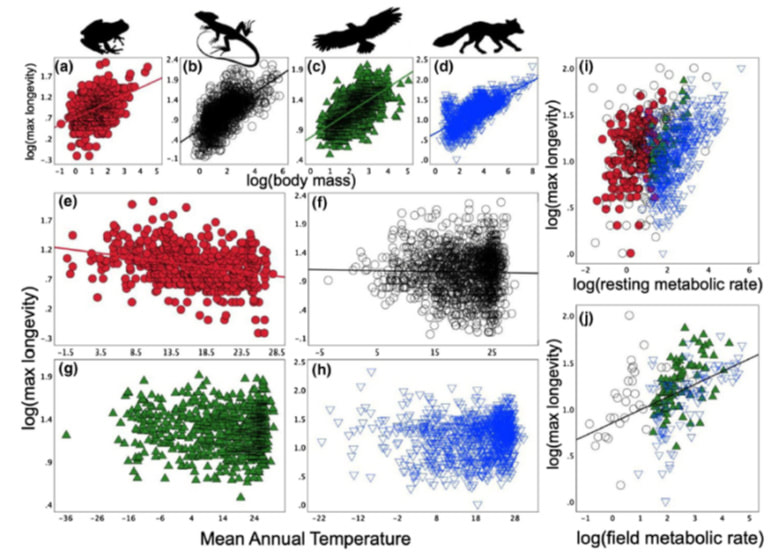

In a recent publication in the Journal Global Ecology and biogeography, we (Gavin Stark; Daniel Pincheira donoso and Shai Meiri) showed that the assumption under the “rate of living” theory which have been around for almost a century is unsupported by the results of our largest scale study (4,100 land vertebrate species: 2,214 endotherms & 1,886 ectotherms) to date of this theory. We could not find any connection between animal metabolic rate and longevity, either when we tested all land vertebrates (i.e. Mammals, Birds, Reptiles and Amphibians) or when we tested each group separately. In contrast, we did find other factor that did affect the lifespan of ectotherms (Reptiles and Amphibians), and it is ambient temperature. In colder regions around the world we expect species of reptiles and amphibians to live longer than other ectotherms living in warmer environments. The link between ectothermic (amphibians and reptiles) lifespan and ambient temperatures could mean that they are especially vulnerable to the unprecedented global warming that the planet is currently experiencing. Indeed, if increasing ambient temperatures reduces longevity, it may make ectothermic species more prone to go extinct as the climate warms. Our findings add a previously overlooked layer to the range of factors that are commonly thought to imperil species in the Anthropocene.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed